RIVERS OF BLESSING: THE WINDRUSH GENERATION AT 75

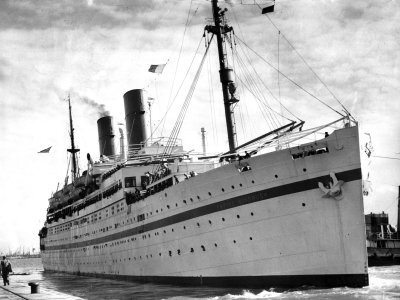

Tilbury docks: the unassuming location of an event that would come to define post-war British society. The disembarking of 429 people from Caribbean islands to begin to fill the big gaps in the labour market after world war and to staff the emerging welfare state has become a symbol few would have expected at the time. And like all symbols, it is invested with different meanings, especially round immigration, identity and injustice.

Windrush came to represent the estimated half a million UK residents who were born in a commonwealth country and arrived in the UK before 1971. Some had served in the armed forces during the war; many would support the newly created National Health Service. This cohort and their descendants have been a deep blessing to the UK in every field: politics, business, media, science, engineering, medicine, academia, music, arts, sport, religion.

The Book of Revelation visualises the new heaven and the new earth we inherit through the resurrection of Christ. It’s a place where Revelation says the ‘glory and honour of the nations’ will be brought into it. At the end of time, the rich diversity of the human race will be woven into a new world. Cultures will harmonise in the song of their lives and glorify God. When cultures mix today, there is a hint of this future.

But we cannot sanitise the story of the Windrush generation. It has been exposed to astonishing levels of racism at different points – ranging from the casual to the violent. There has been discrimination and prejudice. Life chances round education, health, housing and wealth remain unequal between different ethnic groups in the UK. And this is compounded by heartless voices who claim these outcomes are either a mirage or the product of individual, not institutional failings. Every generation seems to raise the hope that racism will become less prevalent, only to disappoint. There are greater hopes for Generation Z than any before, but the human race is not perfectible. Moral vigilance and fairer policies are constant requirements and goals.

Windrush itself became a symbol of injustice seven decades on, when it emerged the Home Office had kept no records of those granted permission to stay, putting long established British citizens at sudden and shocking risk of deportation to countries they had long left or had no memory or even experience of.

In Jeremiah 29, the prophet encourages the exiles in Babylon to build homes, find work, marry and settle down in their new country. For when they did, they would find contentment and acceptance, be blessed and be a blessing to those around them. It is a biblical vision of the integration of different ethnicities and cultures we can draw hope and inspiration from. Imagine pursuing this goal wholeheartedly, only to wake up one day and find a national bureaucracy denying you access to healthcare, work and housing and threatening and implementing deportation.

This was the Windrush scandal that rocked the nation and shook many people to the core who heard the message: this is your country until it isn’t. It has cast a long shadow over well-established immigrant communities, as has the release into public debate of the term ‘hostile environment’. This phrase was aimed at illegal immigrants, and once uttered, was always at risk of being deployed against anyone who arrived in the UK – and especially towards visible minorities. Careless and aggressive language used by public leaders is always picked up by others and weaponised against innocent people.

An investigation into the Windrush scandal was published in March 2020, just as the country headed into lockdown. Its thirty recommendations were accepted by the government. In January 2023, some of these recommendations were dropped by the Home Secretary, including the appointment of a migrants’ commissioner and the holding of ‘reconciliation events’ with victims of the scandal, to listen and reflect on their stories.

Every nation has to create viable immigration policies. Among other things, these must take account of the need for foreign born workers to fill gaps in the economy. The government should ensure existing infrastructures are sustainable for the current population and for those who are adding to it. And it should have generous regard for refugees who are escaping conflict and catastrophe. It would be naïve to say this is an easy task and mistakes will always be made. What is especially important are the underlying values that drive decision making, for these will guide both the tone of communication and the content of policies chosen. This is where many of us hope the Christian faith has traction, even in a nation that has lost its allegiance, because a nation governed in the character of God is a blessing to its citizens. We may not agree on the detail, but welfare and hospitality are front and centre in the story of the Bible.

As is the need for unity. Diversity is deeply important but we should not lose sight of the need for a nation to cohere, to find things it agrees on and supports. This is where Britain is on shakier ground than before, as we face the identity crises highlighted by Scottish nationalism and departure from the European Union. What holds Britain together? It used to be the institutions that many other nations have copied, but these institutions have become damaged and untrustworthy in the eyes of many. In asking immigrant people to become more British, we need to be honest about the current difficulties we have in describing what it means to be British. And when immigrant communities struggle to integrate, to remember the pivotal role host communities play in enabling their place.

In Revelation’s vision of the kingdom of God, it says the gates of the city will never be shut. There will be no fear of outsiders. And in a phrase easily missed, it says the sea will be no more. That may be a serious disappointment for maritime lovers, but Revelation deals in metaphor, of course. The sea was seen as scary and untamed in Hebrew thinking and ancient Israel was never really a sea-faring nation, so it made sense to perceive the kingdom of God as a safe land to live in. But the sea also separates us from others and keeps us apart, and Revelation visualises a world where people mix without having to risk their lives to enable that.

Today is a day to celebrate a small group of people who made a long and arduous journey across the Atlantic, the common humanity we share and the blessings we have received through the risks they took.